First, a disclaimer. This is not going to be a project to give you the “true meaning” of this religious text. This is as with the others, an experiment, particularly for those who live on the edge of these communities, who need a way to reconcile to them without compromising their values. I will be making use of “The Study Quran”, translated by a team led by Prof. Seyyed Nasr1. As Nasr himself says, the original revelation is in Arabic, hence I am at least once removed from the revelation itself, if not twice because it is best recited and not just read. I am not a Muslim and do not claim to be one.

What I am doing here, more concretely, is to see what a polytheist might make of the Quran, in the hopes of an ideal world where such eclectism might not attract violence from some (not all) quarters. It is a bit of relief for me that there are sects of Islam that, like me, hold to Platonism, although we disagree on key details. My approach is to read this as a Platonic Polytheist who wants to see the revelation that this God (or Gods) has for him, through the refracted lens of a translation. The reason I say “Gods” even though Islam is usually the most anti-polytheist of the Abrahamics is because there are indeed forward-thinking Muslims that acknowledge some sort of “polytheism” in the loose sense, in a way that doesn’t compromise Tawhid, according to a certain reading. Corbin has incorporated Proclus into his understanding of Tawhid2, and although I ultimately think it’s not enough, I also think it’s the attempt of a real philosopher dealing with the reality of the multiplicity of religious experience in a way that doesn’t desire to reduce the objects of experience to mere masks or phantoms. This approach, however, is not going to be a shoehorning of the Quran into Proclus’ Platonic Theology. I want to acknowledge a specificity to Islam’s self-understanding, expressed in its rituals, calligraphy, arts, and sciences of all kinds. Thus, the “platonism” I am acknowledging as my bias is more or less “henology”, with the presuppositions that Henads are metaphysically necessary and that the fact of unity “prior” to being means there can be an indefinitude of valid ontologies, Islamic ontologies included. With that behind us, let us proceed to the main part of this prolegomena, in the hopes of an epistrophe.

I

And yet something of the reality of the Prophet’s soul is present in the Quran, and that is why, when asked about his character, his wife ʿĀʾishah replied, “His character was the Quran.”

Seyyed Nasr, The Study Quran. Pg 20

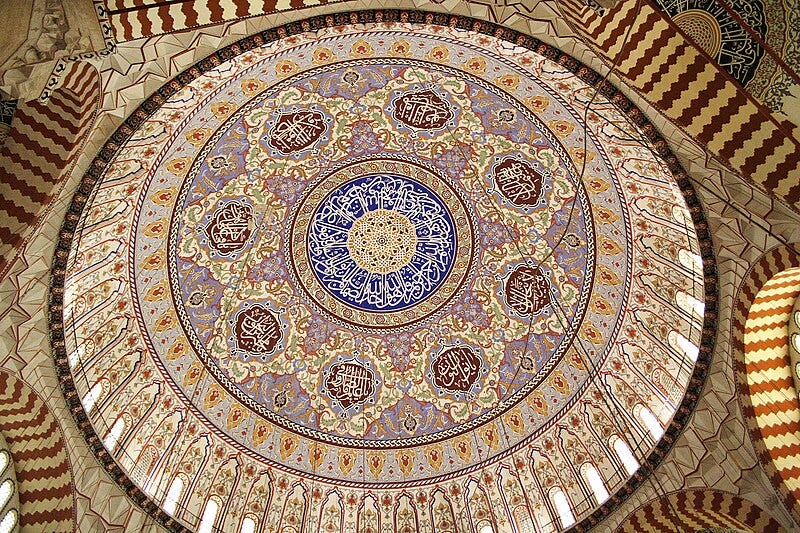

The character of the Quran and Islam that Nasr describes in his introduction is that of a “sonorous metaphysics”. The Quran is recited, sung, and memorized in a manner only Judaism, of the three Abrahamics, approximates. It is also the most aniconic (which we will get into later). Al-Qurʾān means "The Recitation". It is a living myth, a living revelation, the recitation of Allah. What is the recitation of a God but the Worlds themselves? Starting from his very name, the worlds are suspended from the recitation of his attributes. Not just a bland recitation, but a sonorous recitation. The monism of Islam is a monism of song. If Tolkien wanted a model for his Eru Iluvitar, I believe Islam offers something for it. But what does this monism of song have to do with my attempt at a polytheist interpretation?

To quote Corbin:

“Tawhid is to affirm being (wojud, the Act-to be) and to deny the existent being. It is not denying that the existent is existent, but to deny that it is being and to deny that being is existent. It is to deny that tawhid professes the Unity of an existent, for it professes the unity of being, of the Act of being.”3

This Ibn Arabi-inspired interpretation is my starting point for a polytheist consideration of Tawhid. The most robust metaphysical reason for Tawhid is the unity of being itself, the coherence of all that exists. At its best, Tawhid is not a mere affirmation that “My God exists, and all others do not”. This is a trap that leads to a crude atheism, and there are better Atheisms. Instead, Tawhid is an affirmation of the unity of all things, the unity of being, and the divinity of this unity. Proclus gives this definition of theology:

“All, therefore, that have ever touched upon theology, have called things first, according to nature, Gods; and have said that the theological science is conversant about these.”4

If the first thing is the unity of being, that which secures this unity is worthy of being called “divine” and “God”. But, as Schuon notes, this is not about affirming an existent being which may or may not exist in this or that ontology, “the Self”, the divine self, “has no opposite”5, not even “non-being”. This necessarily entails that “God” is not a being, for “Non-Being” is not an opposite to the divine self. But as I have argued elsewhere, this “Beyond Being” of the Islamic Neoplatonic God necessitates the Henads not, as Corbin has is, “Henophanies” of the “Henad of Henads”, but as the polycentric manifold with no monad; that is, qua Henads, they are Gods without a higher “God” of which they are ultimately manifestations.

II

Plotinus argues that even if there is a God who, as a "natural" matter, either rules or even creates the other Gods, this does not affect the "nature," so to speak, of being a God. Plotinus warns against reifying such a hierarchy as an intelligible structure. For if, as in the essay on intelligible beauty, "each God is all the Gods coming together into one" (V.8.9.17), and this clearly is Platonic technical doctrine, as we can see from its elaboration in subsequent Platonists, then the creative moment of which Plotinus speaks when he speaks of a God "abiding who he is, makes many [Gods] depending upon him and being through that one and from that one" (II.9.9.38-40), must exist as a phase in the activity of a God simply qua God, and not limited to some one God to the exclusion of others, in which case there would no longer be a manifold corresponding to Unity, a “numerical” manifold.

E.P. Butler, Plotinian Henadology. Pg 9

The usual response to this “autarky” of Henads is that it opposes monism and thus monotheism. My first (rough) response is to assert that it does not oppose monism. It only qualifies it, such that there can be many monisms, and that monisms and dualisms generate each other whenever we analyze the units enfolded within them. For instance, if all things are a diminution from a monad, there is nothing within the monad to necessitate such a “fall”. It must presuppose a metaphysical “direction” which can accommodate such a descent. This is usually “matter”, which individuates the particulars. This is indeed one problem Islamic Monisms have had to face, as death often means that the soul is removed from what individuates it, resulting in the annihilation of the subject on death, an outcome they sought to avoid in their metaphysics by various means6. The monism thus gives way to a dualism, which resolves into a monism again, when the unity of the objects are reconsidered, and so on and so forth.

My second response is that Monism is not Monotheism, and that although the latter has often led to the former, the reverse is not usually the case (for instance, the Stoics7, Epicureans8, and Aristotelians9). This non-necessity of a Monism-Monotheism identity is what made it possible for the Neoplatonists to critique Stoics and Aristotelians without confusing them for monotheists.

The affirmation of Henadic transcendence is not the positing of a further space of a multiplicity of distinct entities that simply “have unity”, but the affirmation that the unities that hold together the various “points” on the chain of being are not exhausted and overdetermined by those positions and their ontologies, and are “All in Each”. Before there is any cosmic arrangement, the unities must be themselves. Thus Zeus is the World Soul here in this ontology and Intellective demiurge there in another ontology. In fact, there are many “Zeuses” who are the same God manifest fully in several points in Proclus’ “multi-ontological” theological tapestry.

III

In Ibn Arabi’s school of thought, harmony is achieved by the confrontation between monotheism of the naïve or dogmatic consciousness and theomonism of the esoteric consciousness; in short the acceptance of the exoteric or theological tawhid (tawhid wojudi). This is precisely the form that the paradox of the One and the Many takes in Islamic theosophy.

Henry Corbin, The Paradox of Monotheism, Pg 5

There are two main takeaways from my explanation:

Tawhid can be expressed as the divinity of the Henads being “All in each” and not a naive polytheism of accidentally existent gods that rend the unity of being into nonsense10

This “All in each” can lead to a preservation of Islamic Monism insofar as one of the implications is that “the totality of henads is the potency of each”11

The second is very important to me in this project, because it means Corbin’s explanation of a hierarchy from a “God of Gods” from whom the “henophanies”, the eternal intellects/Gods, angels, daimons, etc proceed, can be aptly be described with the Platonism I have in mind, without destroying the formal framework, while also affirming the ultimate multiplicity of Gods in the possibility and reality of other cosmological frameworks, and even the relative privileging of different ontologies within Islam itself, even if these might manifest destructively. In this view, the sonorous worlds of Islam begins with the proper named Allah singing his name forth, from which the Gods, as his “powers”, “attributes”, etc, go forth as ontologically subsequent “singing”. It is Allah’s Project. Perhaps here we have the divine core the monotheism that has so plagued us. While the Hellenic Project is Zeus’12, who is Demiurge for them in one capacity or the other; the Islamic Project, is Allah as Being itself. Perhaps he reveals what is muddled in Christianity with the doctrine of the Incarnation. Rather than a monarch who is managing an ever-expanding polity of already existent free individuals, Allah taking the central stage as the force of Being itself is what characterizes his Project. The intensification of this force on our part into political violence is thus our misapprehension of the pure thisness of Being that is only a “force of Salvation”, the force of the Good and integral Being of each, rather than a confluence into conformity of all. For Allah first sings to Himself. The Muslim’s “Submission” thus, can be read, not just as a cosmopolitical submission to a demiurge (although that is included), but ultimately as the existential establishment of themselves in a unity with their God prior to relation, a return to the “Self” beyond ego. In submission to the Lord, one realizes formal determination. This is the constitution of being as an organized multiplicity. In loving the Lord in Himself, as an end, and not as a means, one realizes absolute unity, unity beyond being, beyond hierarchy and monist dissolution: One realizes the heart of Salvation.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, Caner K. Dagli, Maria Massi Dakake, Joseph E.B. Lumbard, and Mohammed Rustom. The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary. HarperOne; Reprint edition, 2017.

Corbin, Henry. The Paradox of Monotheism. https://traditionalhikma.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/The-Paradox-of-Monotheism-by-Henry-Corbin.pdf

Corbin. Pg 6.

Book I, Chatper III. In Proclus, and Thomas Taylor. The Theology of Plato. Prometheus Trust, 1995.

The Servant and the Union, Pg 47. In Schuon, Frithjof. Dimensions of Islam, 1985.

Riggs, Tim. ‘On the Absence of the Henads in the Liber de Causis: Some Consequences for Procline Subjectivity’. Proclus and His Legacy, no. 1994 (2017): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110471625-021.

“The most integrative philosophical approach in the Hellenistic era was Stoic naturalism, which however preserved the multiplicity and differentiation of phenomena by making its unifying principle completely immanent, so that there was no serious possibility of posing some transcendent unity against the many.” - Butler, Edward P. The Way of Being: Polytheism and the Western Knowledge System. Notion Press, 2023. Pg 113.

Jackson, Paul T. M. ‘The Polytheism of the Epicureans’. Walking the Worlds, 1 January 2016. https://www.academia.edu/36564126/The_Polytheism_of_the_Epicureans.

Bodéüs, Richard. Aristotle and the Theology of the Living Immortals. SUNY Series in Ancient Greek Philosophy. New York: State University of New York Press, 2000.

“The thesis of this dissertation is that Proclus interprets the primacy of unity in the Neoplatonic tradition as the primacy of individuality, and the first principle of Neoplatonism, the One Itself, as the principle of individuation. Furthermore, the One Itself, despite its hypostatization for discursive purposes, is actually not different from each member of the ultimate class of individuals: the One is each henad. Proclus can thus be seen, from different points of view, as a monist or a pluralist, for while there is for him a single principle from which all of reality depends, and in that respect he is unquestionably a monist, that principle is also really many. It is not, however, as many henads that the One is the first principle, for the first principle cannot be many. Instead, the One is the first principle as each henad individually. That is, it is in the uniqueness of each henad that the first principle is manifest, not in that henad’s membership in any group or class.” - Butler, Edward. ‘The Metaphysics of Polytheism in Proclus’. New School University, 2003. https://henadology.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/dissertation-revised-copy1.doc. Pg 3-4

Butler, Edward P. ‘Damascian Negativity’. Dionysius 37, no. December (2019): 114–33. Pg 133

One of the themes of Butler’s course on “Polytheism in Greek Philosophy” is the idea that Hellenic civilization and its cosmos, including its philosophies, is Zeus’s Project. It’s an idea I find incredibly illuminating.

Glad you're doing some analysis on Islam through that henadic lens of yours!

There is something admirable and creatively brilliant in your attempt to read the Qur’an through the lens of Platonic polytheism. You are not trying to prove anything doctrinally. You are trying to see what can be made of the text, when approached from a metaphysical position outside its tradition. That is a reasonable, philosophically honest, and potentially illuminating thing to do.

You acknowledge that your perspective is not Islamic. That is important. You also recognize the limitations of your method—translation, cultural distance, theological divergence. You are asking whether something like the henadic manifold of late Platonism can be reconciled with the Qur’an’s central idea of Tawhid, or divine unity. This is an interesting question.

There is some initial plausibility to the comparison. In certain Neoplatonic systems, unity does not exclude multiplicity. On the contrary, the many derive from the One, and in some cases (as you note in Butler and Proclus), each divine being participates in the structure of the whole. The Henads are not parts of a unity, but each in some sense *is* the unity, in its own mode.

Tawhid, at least in some interpretations—especially those influenced by Ibn Arabi—is not simply the denial of other gods. It is the affirmation that all being is one being, and that this unity is divine. On that reading, it is possible to treat multiplicity as secondary, or derivative, without denying it altogether. This could make room for something like polytheism, depending on how one defines the term.

Still, there are problems.

The Qur’an is not a philosophical treatise. It is a revelation that speaks in commands, affirmations, warnings, and stories. It does not present Tawhid as a speculative unity beyond being. It presents it as the sovereign reality of a named God—Allah—who gives law, judges nations, and demands obedience. The text repeatedly and explicitly rejects the attribution of divinity to others. That rejection is not merely metaphysical. It is moral and legal. To associate others with God (shirk) is the greatest error. That message is structurally central to the Qur’anic worldview.

You are reading the Qur’an philosophically, which is fine. But you are also subtly transforming it in the process. You are extracting a metaphysical principle from a text that embeds it in a network of historical and legal commitments. It’s worth asking whether that principle survives the extraction.

You also seem to want to preserve something of Islam’s monism by interpreting the divine name as a kind of cosmogonic recitation—Being itself, singing forth the world. That is a strong image. It bears resemblance to certain Neoplatonic ideas about procession and return. But the Qur’an’s recitation is not just a metaphysical act. It is a communicative one. It addresses a people. It enters into history. That distinguishes it from the anonymous generativity of the One.

There is a more general philosophical question here. Can radically monotheistic and polytheistic systems be reconciled, even at the level of metaphysics? Or are they based on incompatible intuitions?

Monotheism emphasizes order, sovereignty, and the moral unity of reality. Polytheism emphasizes difference, multiplicity, and the irreducibility of divine presence to a single form. Both approaches have strengths. Monotheism supports the idea of a rationally intelligible cosmos, governed by a single source. Polytheism better accommodates the variety of experience, the fragmentation of value, and the unevenness of the sacred.

If we take Schopenhauer’s idea of the Will (der Wille zum Leben) as fundamental reality or noumenon, there is a way to reinterpret both systems. The One could be the structure of striving itself, the unified directionality of all becoming. The gods, or Henads, could be manifestations or even simply symbols of that striving in distinct forms. In that case, neither monotheism nor polytheism is literally true. Each becomes a symbol system for articulating different aspects of a deeper and manifestly ubiquitous process. Nothing and no one escapes it, if Schopenhauer is correct.

This is a kind of non-theistic metaphysics. It does not deny the sacred, but it does relocate it. Divinity becomes a mode of understanding the structure of reality, which is not a person, and not a set of persons, but something more abstract and impersonal. It may still call for reverence but not submission.

Your project seems to move in this direction. You are trying to salvage the beauty and power of Islamic metaphysics without adopting its theological commitments. You are not dismissing the tradition. You are trying to think with it.

That is a worthwhile effort. But it comes with limits. The Qur’an does not easily lend itself to this kind of philosophical abstraction. It insists on a particular God, a particular people, and a particular path. Reading it otherwise may be illuminating, but it is not a neutral act. It transforms what it reads.

That may be acceptable. Philosophy often does this. But clarity about one’s position helps. You are not interpreting the Qur’an within Islam. You are encountering it from outside, with a different metaphysical vocabulary. That is honest work. And it might reveal something new, not about what the Qur’an says but about how it can be received by those who seek meaning without conversion.

In that sense, your experiment may serve as a kind of bridge; it is not a theological bridge but rather a philosophical one. For those who do not believe in God, but who take seriously the ways human beings try to speak of what is ultimate, this kind of work is truly worthwhile.